Bowen Chen

Scott Gerring

In the late 2000s, the big question in database design was SQL or NoSQL. While relational databases had long held their ground, document and key-value stores were emerging as serious alternatives. Many predicted a zero-sum, winner-take-all outcome. But when we look at how organizations are using database technologies today, no single tool or category has dominated the landscape. In fact, many organizations have adopted multiple databases to handle different sets of challenges, reflecting the industry’s broader shift towards microservice architectures.

The rise of microservices has quietly redefined the way companies use databases. Databases are no longer monolithic backbones. Instead, they’re fragmented across hundreds of services that share or maintain their own data storage. For monolithic architectures, the question of SQL versus NoSQL seemed more critical. A single shared database governed all application components, and selecting the database that best fit every feature or component could significantly improve cost-efficiency and performance. However, in microservice architectures, each team has the flexibility to adopt the solution that best addresses the needs unique to its service. While this makes the strategic selection of a single database irrelevant, it presents its own challenges that organizations are dealing with today.

With visibility into tens of thousands of customer stacks, we’re able to not only tell the story of this shift but also show you the data to back it up. For this blog, we analyzed Datadog APM service and integration data from over 2.5 million services in the past year. We’ll discuss how microservices have changed the way organizations use and think about databases and how these changes are reflected in their technology stacks.

Monolithic architectures and the shared database model

To understand how microservices have influenced the adoption of different database technologies, we first need to understand monolithic architectures, their history, and their challenges.

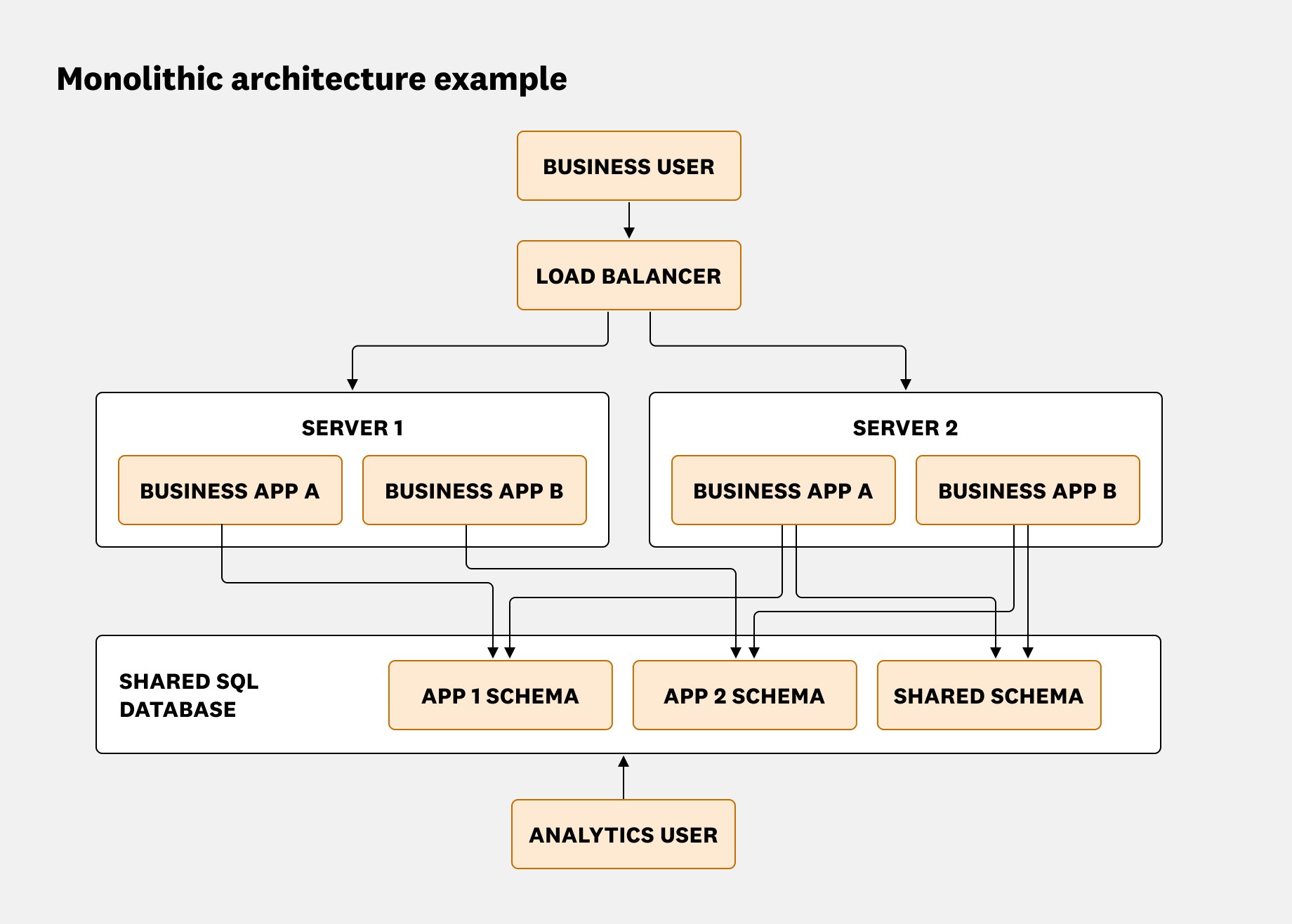

Around the time that non-relational databases (NoSQL) began to gain popularity, monoliths were the dominant application architecture. These applications often shared a common database that acted as an integration point between monoliths and their components. The following diagram shows how this works:

Typically, the business user or the end user of your application sends queries to a load balancer, which distributes requests between your different application servers. All of these business applications query either dedicated or shared schemas within a single shared database. As a result, the shared database becomes an integration point for applications. Rather than relying on API calls to communicate, applications reference shared tables, and when data changes or new entries are added, triggers and stored procedures built into the database automatically perform follow-up actions. This model also guarantees strong data consistency. Transactions across tables either succeed or are rolled back to their pre-existing state, and all operations that threaten referential integrity are either rejected or handled via cascading deletes.

Having a single source of truth that is always correct and up-to-date is a strong motivation for the shared database model. However, allowing applications to rely on shared schemas also adds coupling complexity. Each new schema update becomes a coordinated effort across the engineering organization to ensure compatibility for all the dependent applications, and this can greatly slow down development velocity as your number of applications and teams grows.

The benefits of microservice architectures

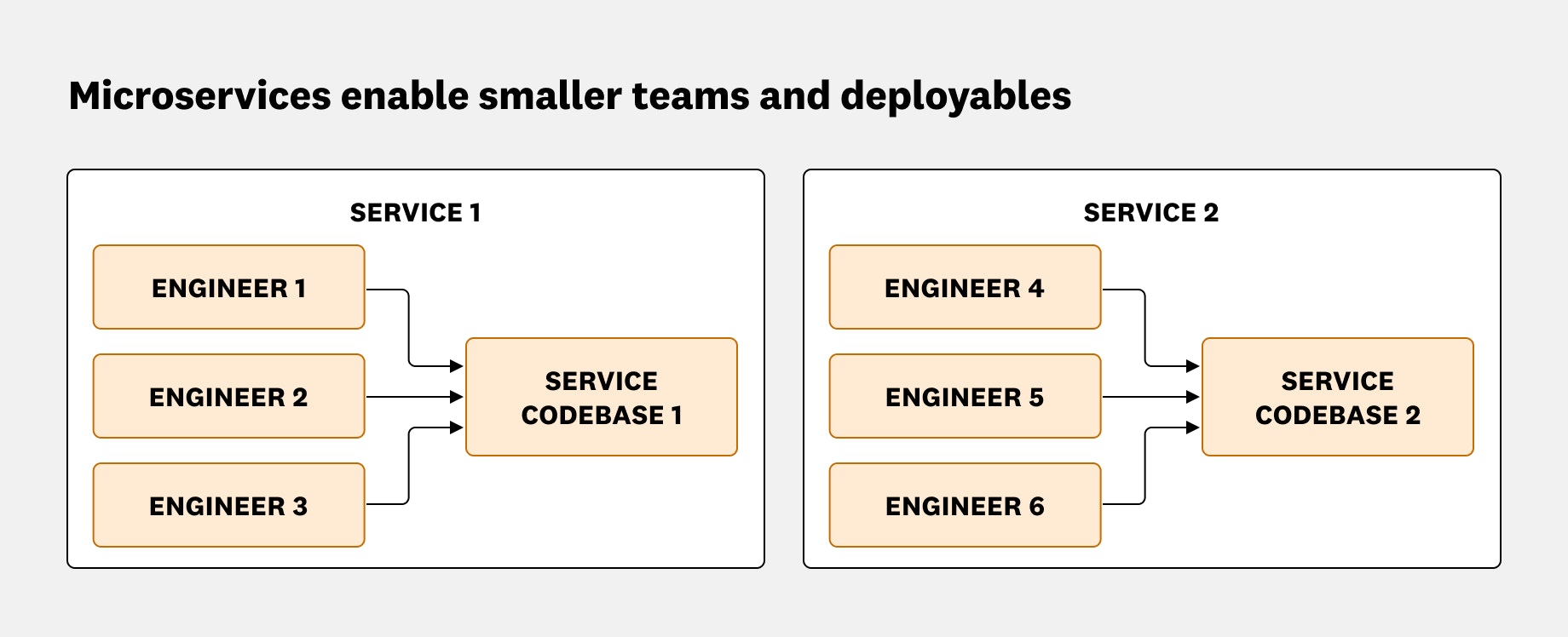

Microservice architectures emerged as a technical solution to this organizational problem. By decreasing the size of the deployable artifact (the service itself) and reducing the number of engineers working on each component, organizations can continue scaling their engineering teams and create faster release cycles without the risk of breaking another team’s code in a shared codebase.

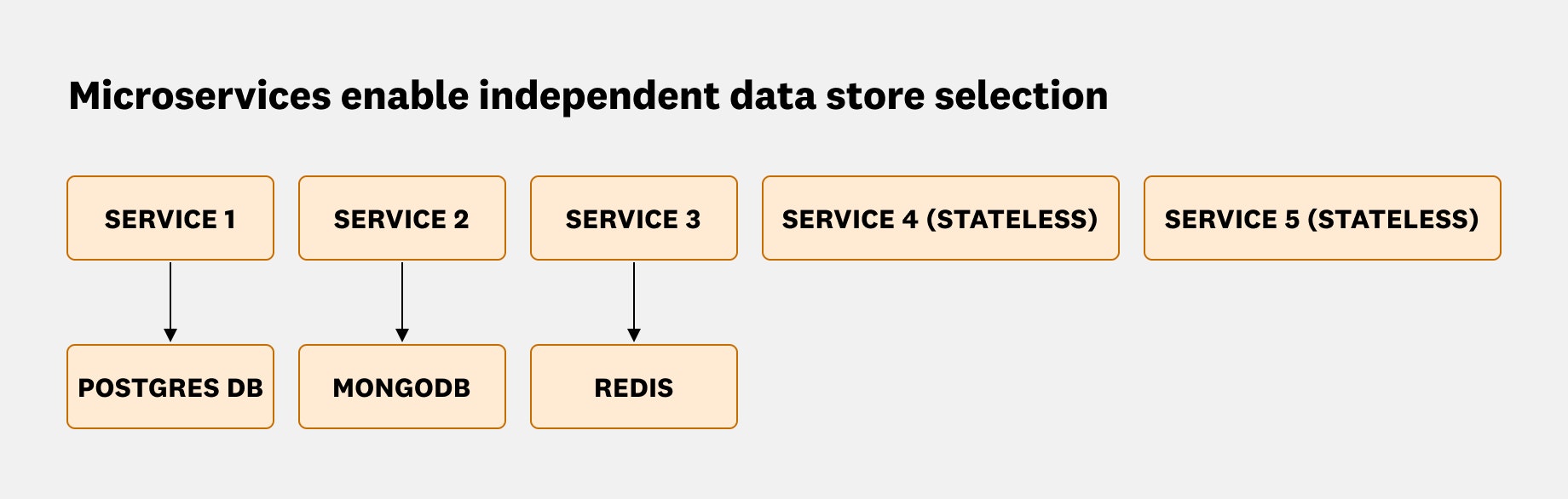

As the industry has embraced microservice architectures, the decision of which database to use can now be made repeatedly, once for every service rather than once at the organizational level. Under this approach, services and their owners have the flexibility to choose data stores independent of the schemas and models of their organization as a whole.

While this offers teams more versatile development options, it doesn’t mean each team is always required to adopt their own database solutions. Organizations that have platform engineering teams often operate fully managed database platforms that offer golden paths to developers and help them adapt their use case to a standard schema within a shared database cluster.

Database adoption patterns in today’s landscape

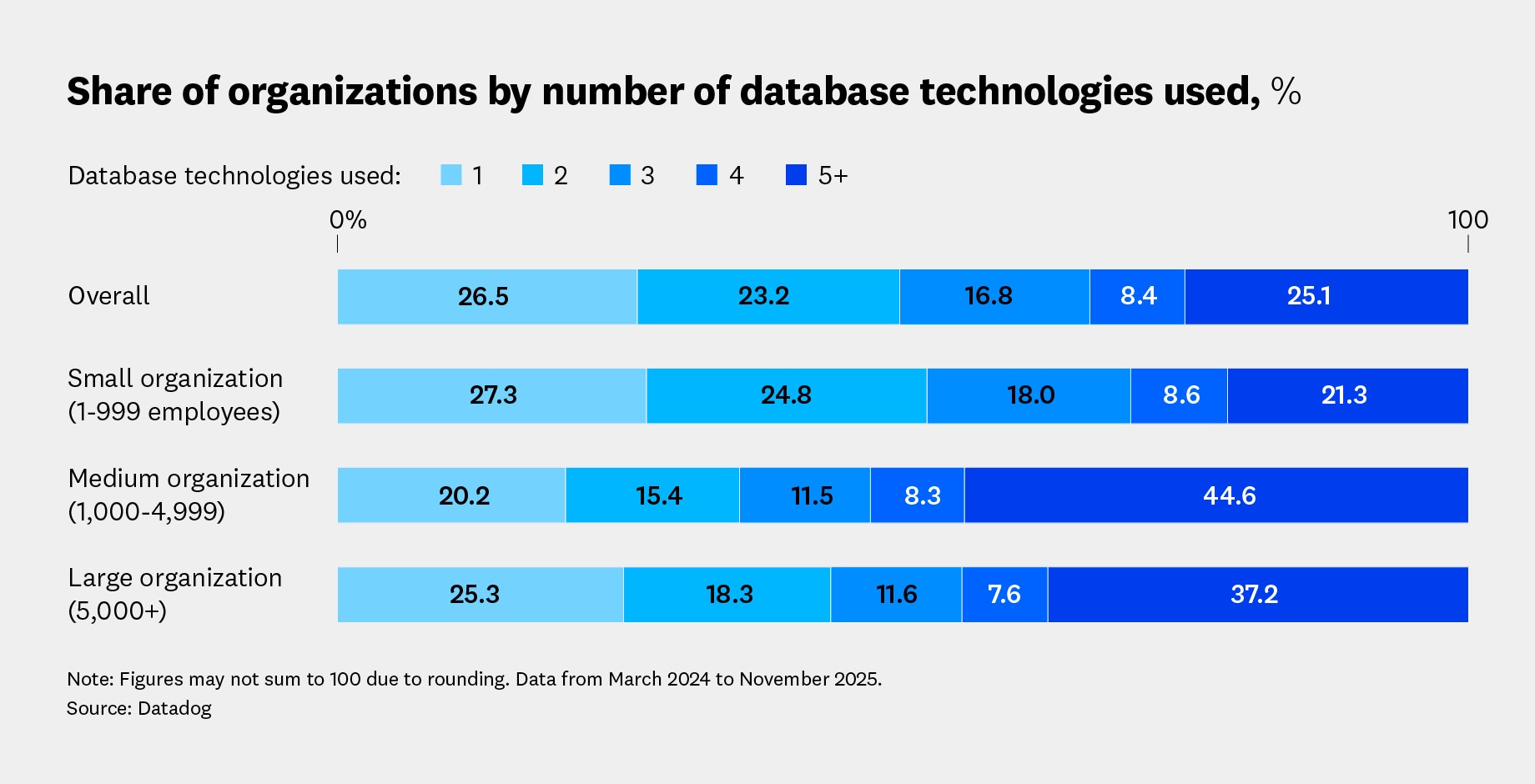

We can see some of these trends reflected in our customer data. Organizations have begun to embrace the idea of using different databases for different tasks, with more than half of all customer organizations adopting three or more database technologies in their stack. What’s even more interesting is that a quarter of customers are now using five or more databases, nearly matching the share of organizations that still rely on a single database.

The data paints a clearer picture when we group database adoption by company size. Of those that have adopted five or more database technologies, we see a mix of predominantly those that are medium and large in size. Many medium organizations that exist today were built from the ground up using microservices. On the other hand, large organizations often began with monolithic, on-premises architectures and have since migrated their workloads to the cloud. This places them on the far right of the spectrum in terms of technical maturity. To further optimize their workloads, they’ve adopted different databases for different application use cases.

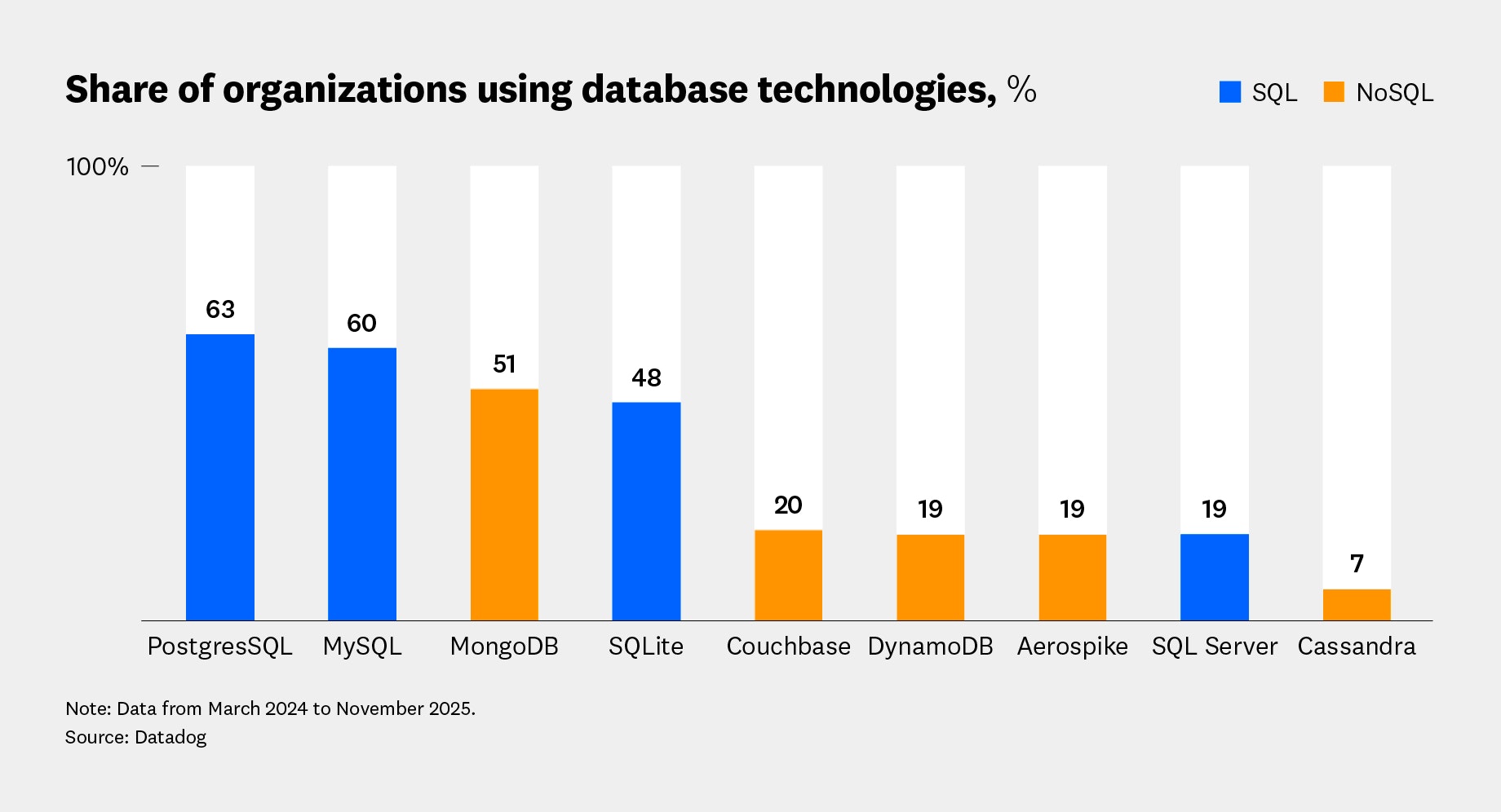

This shift toward a wider range of database tools has enabled organizations to adopt a “right tool for the job” approach. Rather than using commercial relational databases like Microsoft SQL everywhere, they are starting to mix in other classes of databases. More customers now use open source SQL databases such as PostgreSQL and MySQL, which are often more cost-effective and flexible than traditional commercial SQL solutions. We also see strong adoption of NoSQL databases such as MongoDB, Couchbase, DynamoDB, and Aerospike.

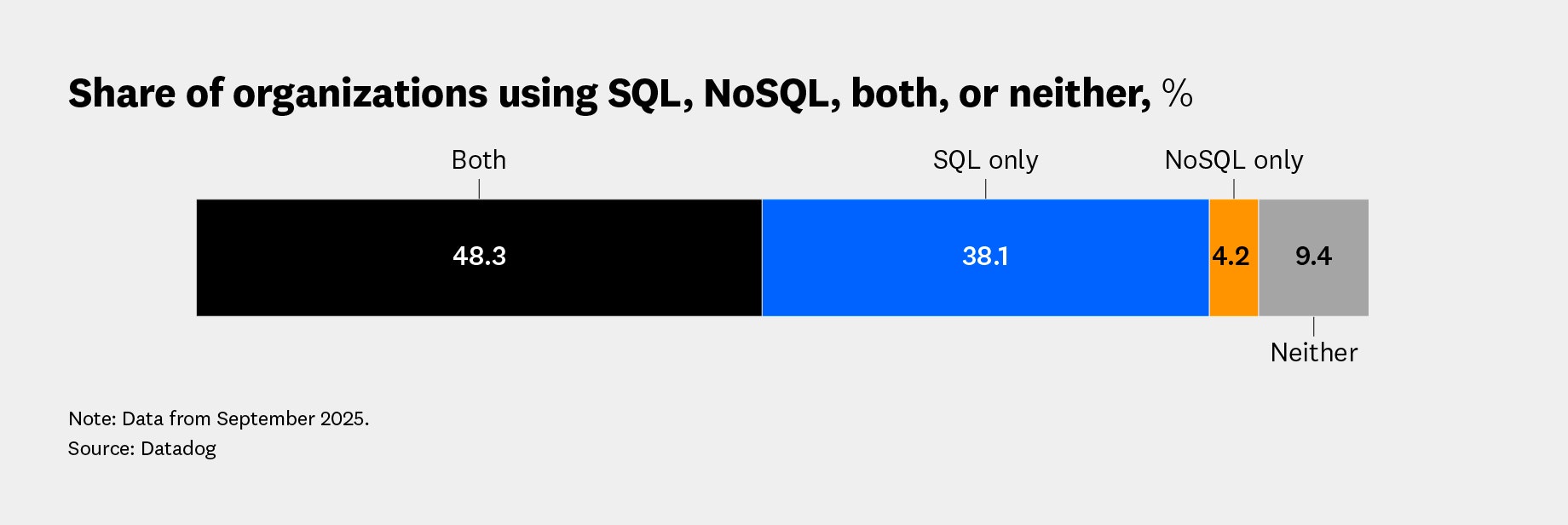

Additionally, the use of SQL and NoSQL is no longer mutually exclusive. While it was once uncommon for an organization to use both SQL and NoSQL databases due to their differences, we now see this behavior from nearly half of our customers.

Workloads that require strong transactional consistency and structured data, such as inventory management or banking, are still best fit for SQL. Meanwhile, NoSQL is best suited for handling high-speed workloads and diverse datasets, such as real-time internet personalization and product catalogs.

A new set of challenges

Using multiple databases across one organization still comes with challenges. Many of the reasons this model was once considered unworkable—such as the lack of a single source of truth, differing schemas, and weaker service integration—did not just disappear as organizations shifted to microservices. In this section, we’ll discuss these obstacles and the tools we see customers use to address them.

More databases = more schemas = more service-level joins

By embracing microservices, organizations fragment one global schema into hundreds (or even thousands) of micro-schemas. Rather than acting as a shared artifact that both analysts and developers rely on, database schemas become a private implementation detail of the service they’re tied to. The main issue that arises from this shift is how to join data that spans across different services and schemas.

One solution we’ve seen address this problem is the usage of a data integration layer such as GraphQL. This approach fetches data from multiple data stores and APIs, combining their schemas under a unified GraphQL API schema. As services rely on GraphQL to aggregate data from an expanding pool of sources, much of the relational and join logic once handled inside the monolithic database is pulled upward into the data integration layer—specifically into how GraphQL resolvers are instrumented to fetch the requested data.

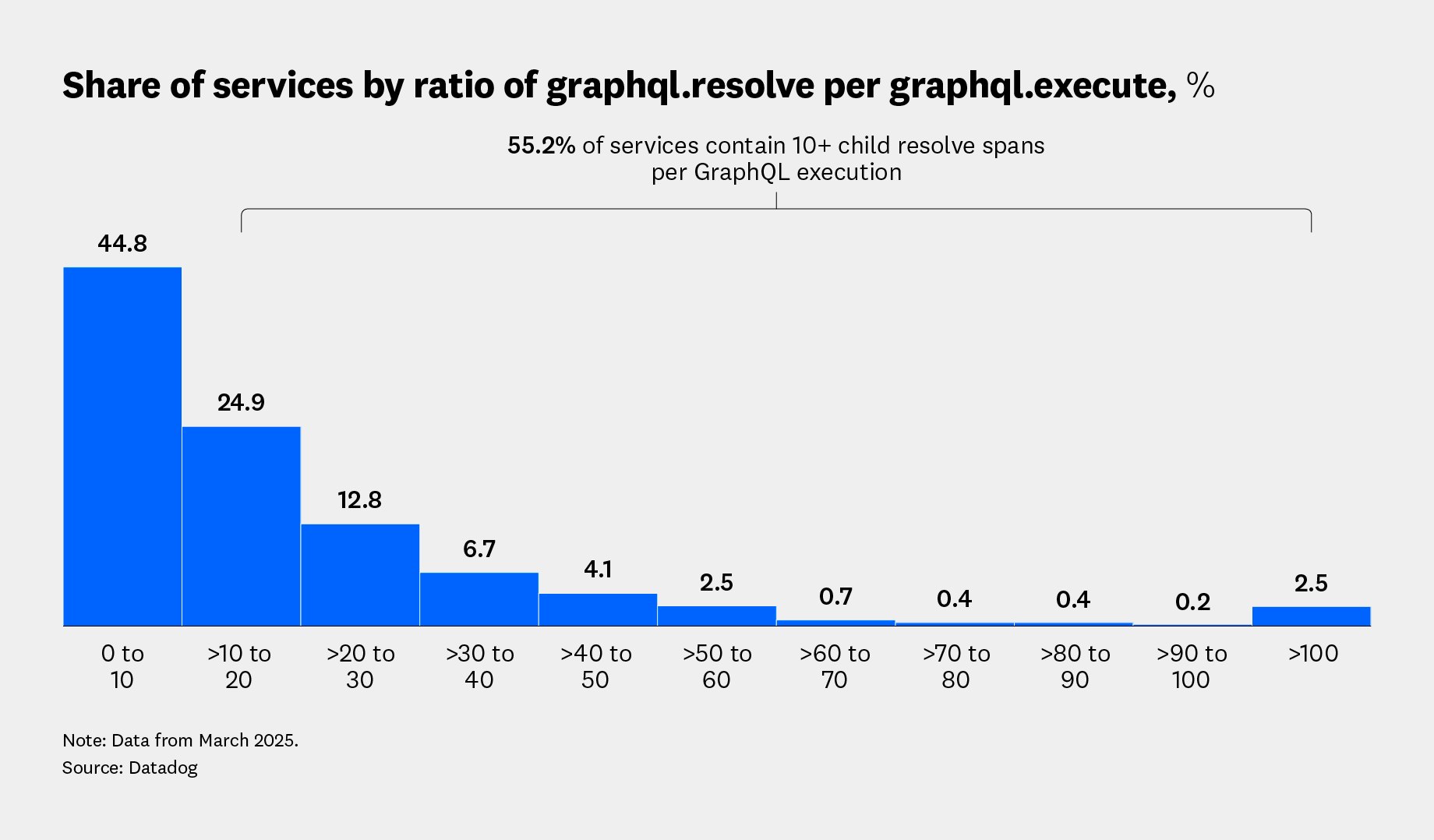

Our data shows that out of all customer services making GraphQL queries, 55% of these GraphQL executions contain more than 10 child resolve spans, with several services handling over 100 resolves per execution. For services that require large volumes of resolve operations, configuring the GraphQL server with optimizations such as batching or caching can significantly improve performance. For example, when querying data for 100 users, a naive GraphQL execution may trigger 100 separate downstream calls. Using a batching utility such as DataLoader combines these separate calls into a single backend query, reducing redundant I/O and keeping resolvers efficient even as the schema grows more intricate.

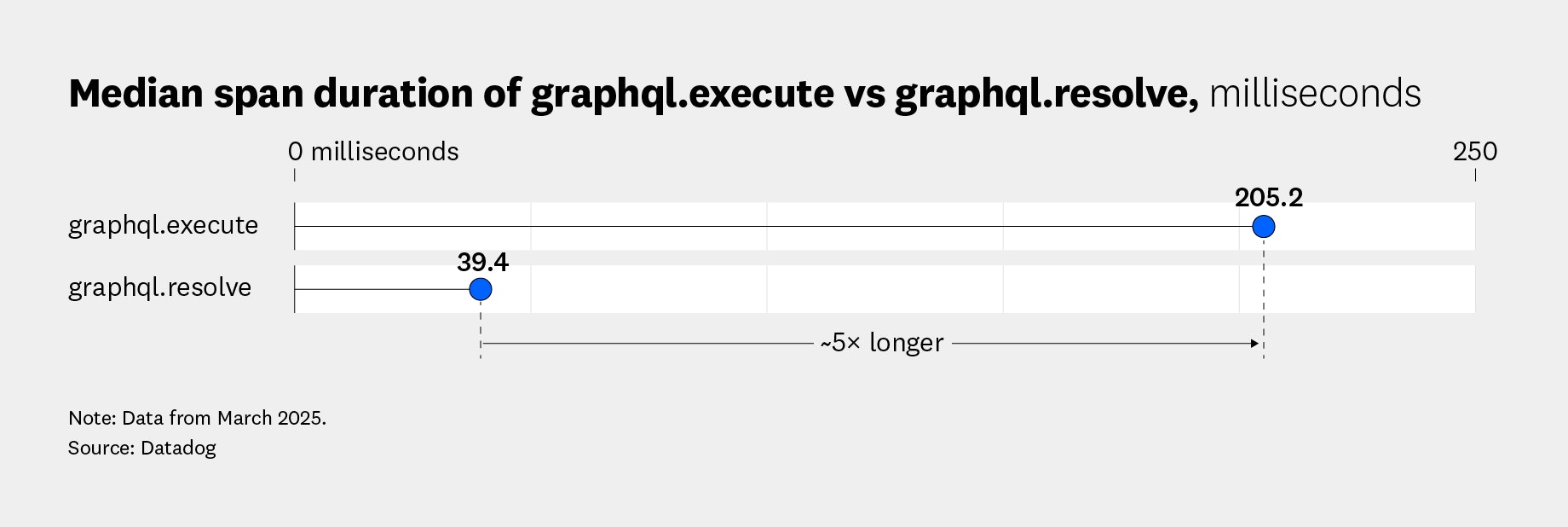

This added complexity within GraphQL executions also introduces a new structural cost related to query depth. GraphQL executes requests breadth-first, resolving each level of nested fields before moving to the next. While fields within a single level can run in parallel, deeper nesting increases the number of sequential steps required to complete a query. In our data, the median GraphQL execution (graphql.execute) takes around 200 ms, while individual field resolutions (graphql.resolve) complete in roughly 40 ms. The gap reflects how GraphQL efficiently parallelizes work within each layer but still incurs a cost for traversing additional layers of schema depth. Minimizing unnecessary nesting helps keep the integration layer responsive without overcomplicating the mapping logic that has replaced traditional database joins.

Analytics is now more difficult

The shared database model allows you to treat analytics as a separate role that accesses the database cluster. Storing all of your data in one place simplifies a lot of analytics problems. Under microservice architectures, however, organizations often use multiple databases simultaneously, each with its own schema and format. To perform analytics, data from these distributed systems must be transformed into a consistent schema and consolidated in a central data store—typically a data lake, a data warehouse, or a hybrid solution. This kind of database system is commonly referred to as Online Analytical Processing (OLAP), and it’s dedicated to handling analytical queries. This separates it from transactional databases built to be highly concurrent, Online Transaction Processing (OLTP) systems, which are better at handling day-to-day business operations.

To establish OLAP systems, organizations have adopted cloud data platforms such as Snowflake and Redshift to serve as large-scale data warehouses. By looking at a shortlist of nine data platforms1 Datadog integrates with, we see 44% of organizations using at least one of these analytics solutions. Unlike the shared singular databases used in monolithic architectures, these systems are not meant to power live applications. Instead, they provide cost-effective storage and highly parallelized, read-only performance for analytics workloads.

Service integration just got harder

Another byproduct of microservice architecture is increased network complexity. Microservices need a way to communicate with each other, but they can no longer do so within a singular application boundary using a shared database or in-memory method calls. Part of the solution has been an increase in the number of synchronous calls between services—for instance, using HTTP, REST, or gRPC—but relying on synchronous communication also creates fragile systems. If services are synchronously coupled, when one service fails to respond, it can create a cascading reaction that affects all upstream services.

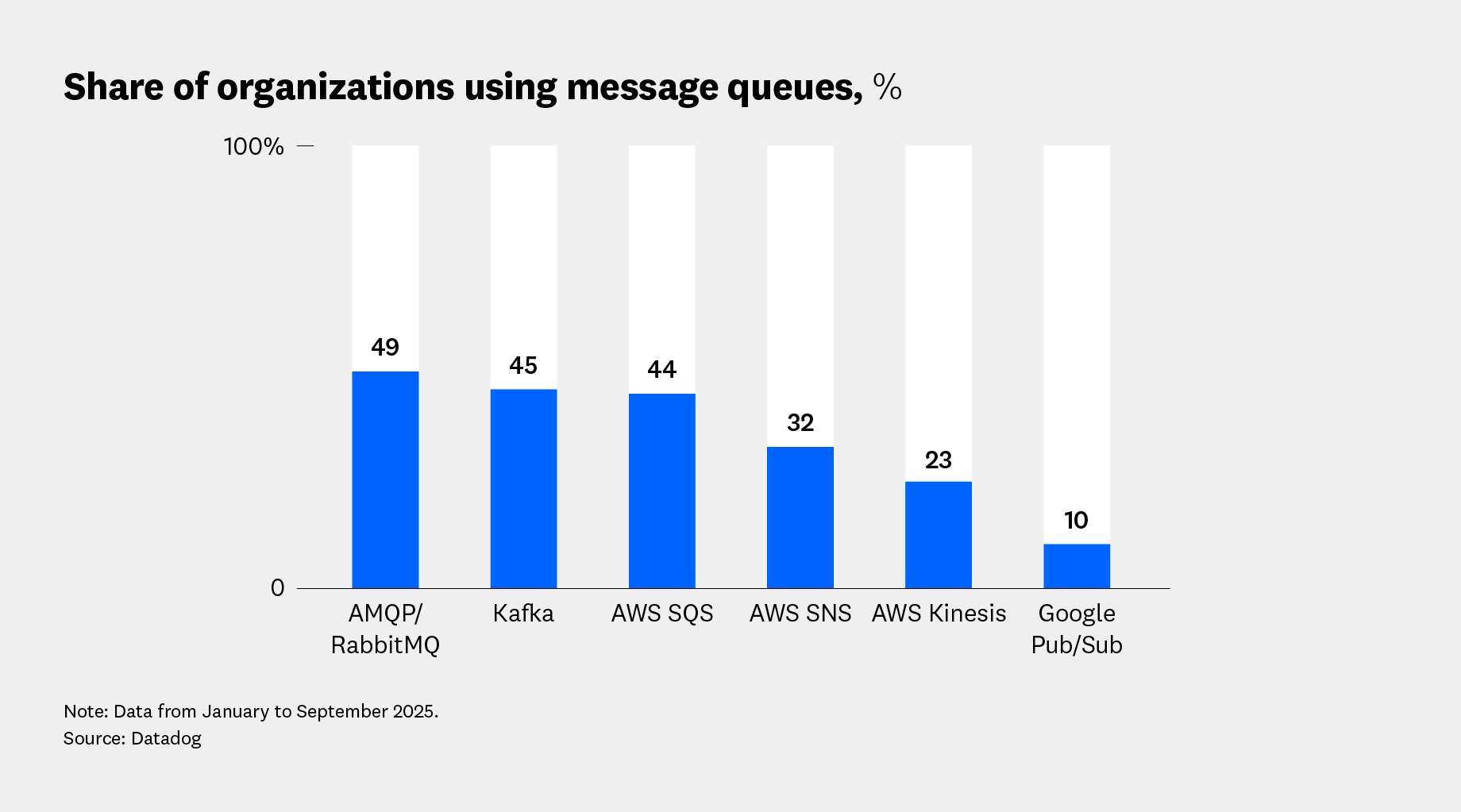

To address this issue, we see nearly 70% of customers adopting message queues. These queues enable services to decouple from one another and communicate asynchronously. Services can publish events without waiting for a response from downstream consumers. This greatly increases system resiliency. During traffic spikes, messages are held in a queue and consumed once downstream services recover. When failures occur, this prevents them from cascading to other services, allowing responders to focus their recovery efforts.

Among message queue technologies, RabbitMQ, Kafka, and AWS SQS show the highest adoption. This indicates that customers are still largely using message queues to decouple their microservices using AMQP protocol but are also moving toward event-driven architectures that use data streaming platforms to perform analytics in data warehouses.

Gain end-to-end visibility across all of your database technologies

Microservices changed the way we build software, and as a result, organizations have had to change how they use databases as well as which databases to use. Based on our data, we see customers today move past the SQL versus NoSQL debate to run both categories of databases side by side. As organizations now adopt more database technologies to handle different use cases, the fragmentation of schemas and data has encouraged the growth of more efficient data integration layers and event-driven architectures.

Datadog Database Monitoring helps you identify issues and optimization opportunities in your databases including PostgreSQL, MySQL, SQL Server, Oracle, and MongoDB. Datadog Data Streams Monitoring helps achieve end-to-end visibility across streaming technologies, integrating with Kafka, RabbitMQ, and more. If you’d like to read more research-based content featuring insights based on our customer stacks, check out our research reports.

If you don’t already have a Datadog account, sign up for a free 14-day trial today.

Footnotes

-

Amazon Redshift, product analytics Redshift, Snowflake, Snowflake web, Databricks, Google BigQuery, Azure Data Lake Storage, Vertica, ClickHouse. ↩