John Matson

This is the third post in a series about visualizing monitoring data. This post focuses on suboptimal graphing practices and how to avoid them.

In the first two parts of this series, we introduced you to several different visualization types—both timeseries graphs that have time as the x-axis, and summary graphs that provide a summary view of a time window.

In this article we show you three ways that these visualizations are often misused and then suggest better solutions.

Anti-pattern: Phyllo graphs

One of the most common goals in monitoring is understanding the behavior of groups. Whether it’s a group of servers, containers, or devices, you want to monitor several entities doing the same job. Ideally, you want to see overall group performance in aggregate, while also keeping an eye on individual performance.

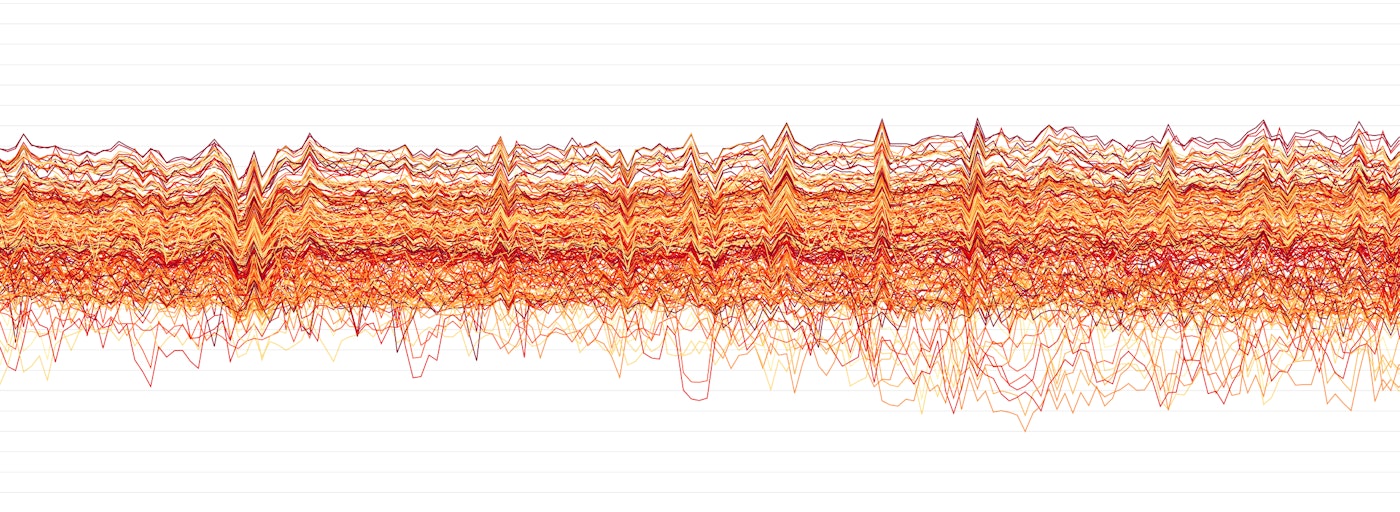

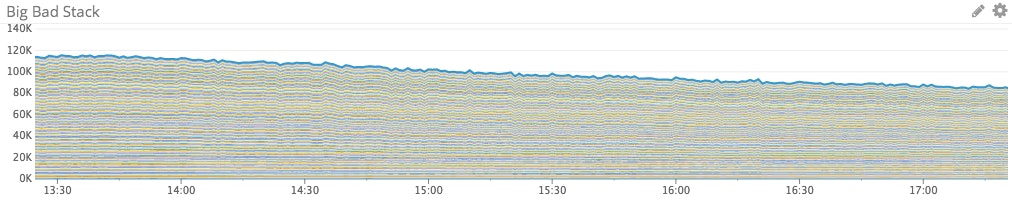

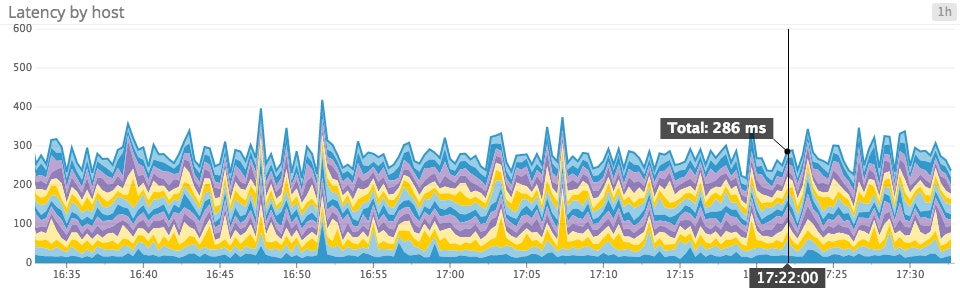

At first glance, a stacked area graph like the one above seems perfect for this use case: The total stack shows you the aggregate behavior, while the individual bands let you see what each member is doing.

The problem: Too flaky to be meaningful

Stacked areas are great for relatively small groups, but become less effective as the size of the group increases, adding bands to the graph. The trade-off for packing more data from individual group members into the same space is, of course, that you lose vertical resolution. Before long your graph has so many layers that it starts to look like phyllo dough.

For really large groups, each band in the group is only a few pixels high, so only the most dramatic differences will be visible at the individual level. These graphs can also slow down your monitoring UI: with every refresh, you’re downloading and rendering a lot of information in the browser that isn’t really actionable.

The solution: Don’t be stingy with your graphs

You need to be able to interpret each of your graphs as quickly as possible. So the solution to an overloaded graph is either to reduce the amount of information in the graph or to spread that information over multiple graphs.

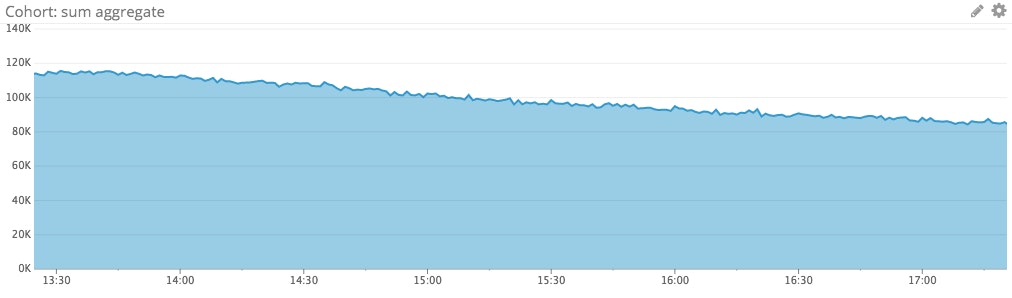

Use an aggregate timeseries graph for the big picture…

A single series showing the sum of group behavior is a much cleaner and more responsive way of tracking aggregate behavior than a sumptuous-looking but ultimately messy phyllo graph.

…Plus a focused look at individual behavior

To highlight individual behavior, you can then complement the aggregate graph with some combination of the following graphs:

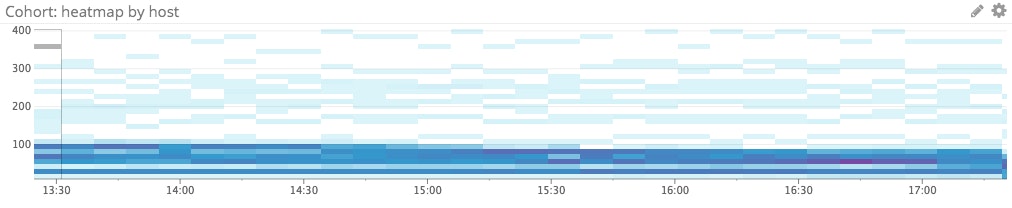

Heatmap for trends

Use a heatmap to reveal general group trends and help you spot outliers.

Host map for current snapshot

Use a host map to show what is happening across the group right now and to segment your group by any relevant attribute.

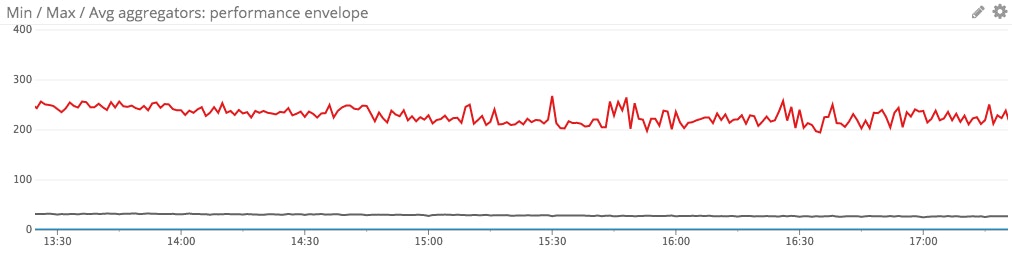

Line graph for performance envelope

Use a line graph of the average, max, and min values across all members of the group to track the performance envelope over time.

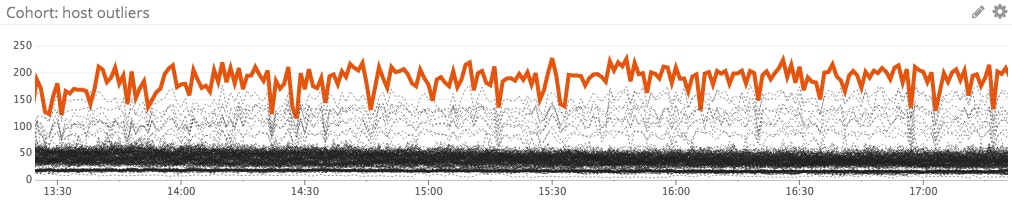

Outlier detection for rogue hosts

Use an outlier detection graph to automatically identify hosts that are deviating from the norm.

Divide and conquer

By splitting an overburdened phyllo graph into multiple visualizations, you’ll have a much clearer picture of what’s happening in your infrastructure. And even though you’ll have more graphs, you should find your dashboard lighter and more responsive in the browser.

Anti-pattern: Using one tool for everything

Timeseries line graphs are fairly general-purpose and are often used by default. With easily understandable axes (time versus metric value), they make sense in almost any graphing context. But just because a Swiss army knife is handy doesn’t mean it’s the right tool for every job. Similarly, line graphs are often used when another visualization type would be clearer.

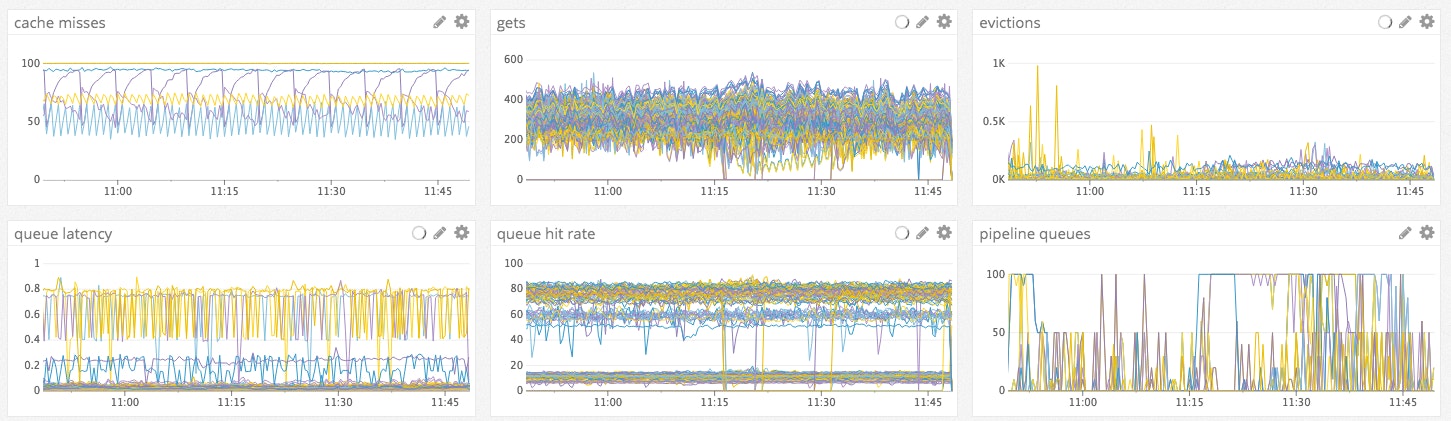

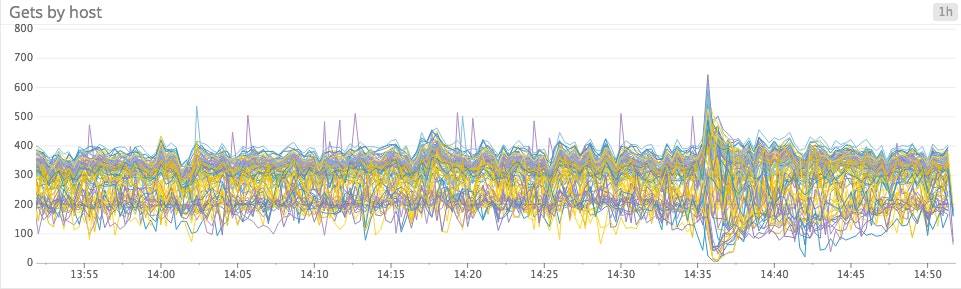

The problem: Spaghettification

Just like stacked area graphs, line graphs lose their usefulness when too many separate timeseries are rendered in one graph. In this case the issue is separation of timeseries. With dozens or even hundreds of lines overlapping and intertwining, you have no chance of tracing the evolution of any one series.

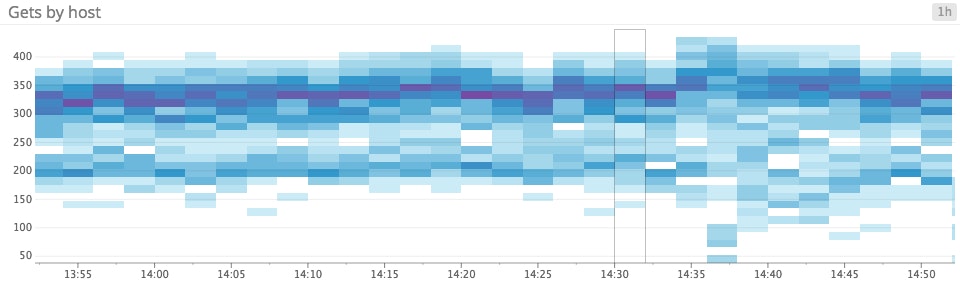

The solution: Turn up the heat

Heatmaps are incredibly useful for monitoring large groups of hosts, containers, or other unit of infrastructure. They allow you to track overall trends while also spotting outliers and anomalies. Heatmaps are purpose-built to clearly render overlapping timeseries—one of their principal features is the use of shading to represent the number of entities reporting a metric in a specific range.

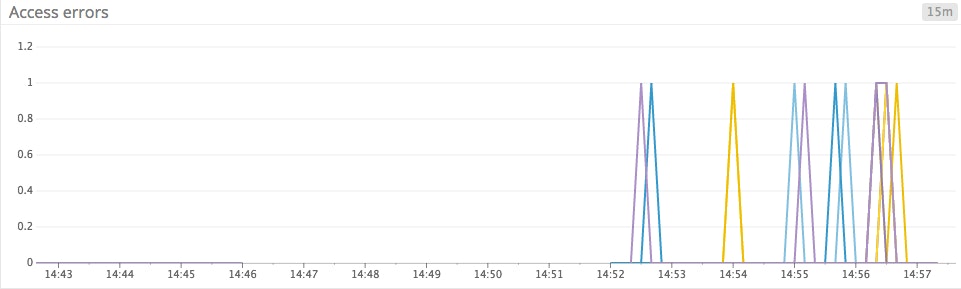

The problem: Jumpy lines

Line graphs are often used to track any metric that changes through time, without much thought given to how that metric changes through time. Line graphs are a poor choice for sparse metrics, because your graphing system will try to interpolate between points that aren’t smoothly continuous. The result is jumpy, spiky, busy-looking graphs that make it harder to see actual peaks and troughs.

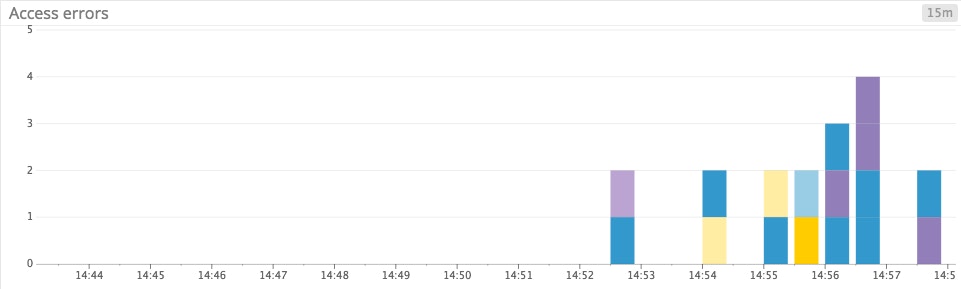

The solution: Raise the bar

Bar graphs are perfect for sparse metrics because they don’t presume continuity. The bars in a graph are discrete elements, rendered without interpolation, so a sudden jump in a metric’s value won’t result in a misleading “trend” line connecting two disparate data points.

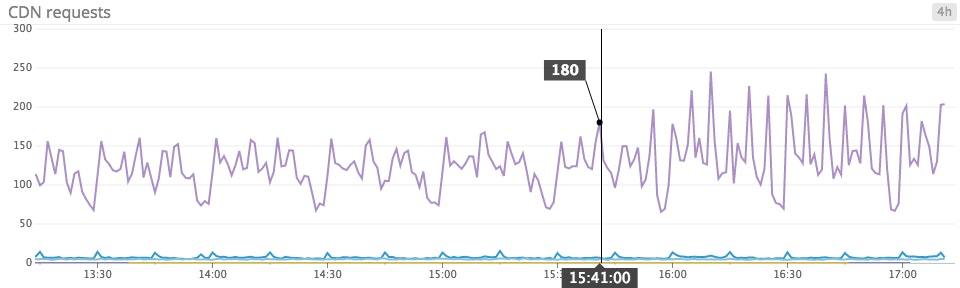

The problem: Counting woes

Line graphs are often used to track metrics that are reported as counts, which can produce confusing data points if you’re not careful. A count only makes sense when paired with a time window (e.g. 73 server errors in the past 1 minute), whereas line graphs are designed to render instantaneous measurements, or gauge values (e.g., 124 database connections currently active). You can render a count using a line graph by first converting it to an instantaneous rate (e.g., 1.2 server errors per second), but you must make sure that your graphs clearly reflect that conversion to prevent confusion.

In the graph below, the unit of measurement is unclear–is it 180 requests per second, or 180 requests over some unspecified sampling window?

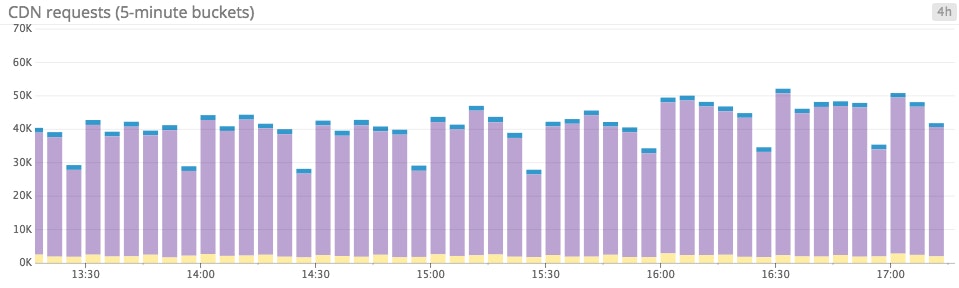

The solution: Keep it absolute

Bar graphs come to the rescue again in this use case. Bar graphs are perfect for rendering counts precisely because each bar has a nonzero width on the x-axis—meaning that each bar naturally covers a definite interval of time. What is more, bar graphs of counts display absolute numbers, which are often quite useful. For instance, if your users start experiencing login failures, you probably want to know exactly how many users have been affected, rather than how many users per second are having issues.

Anti-pattern: Summing something that shouldn’t be summed

Stacked area graphs are sometimes used as a workaround for the spaghetti graphs described above. By switching from a line graph to a stacked area graph, you’re effectively offsetting the y-axis of each timeseries to prevent overlap. Voilà: visual clarity. Right? Well… not always.

The problem: 2 ms + 2 ms ≠ 4 ms

Stacked area graphs break down sums into their component parts (e.g., requests per second per data center), but many metrics simply don’t make any sense as sums. For instance, latency metrics shouldn’t be summed across a group (having more servers reporting latency metrics does not mean your system has more latency), nor should percentage metrics such as CPU.

The solution: Attack the stack

Line graphs and heatmaps render each timeseries separately, so you won’t be adding values from different timeseries when you shouldn’t.

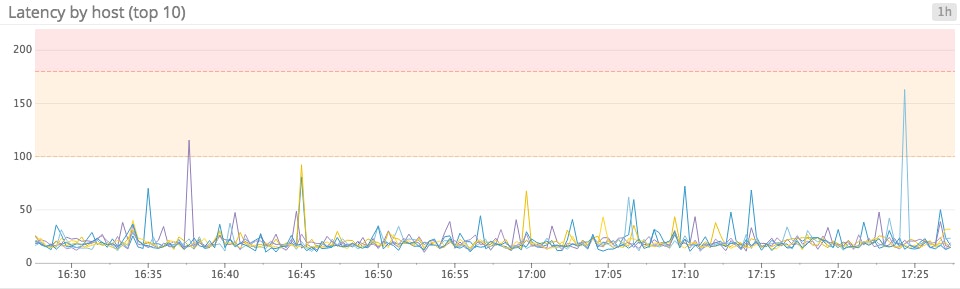

Line graphs when precision matters most

For metrics such as latency, where you might have clear acceptable thresholds and/or SLAs to uphold, line graphs are ideal because they make it easy to identify exactly where a metric stands in relation to your thresholds. The keys to plotting many timeseries on one readable line graph are aggregation and filtering: you might plot the average from all your hosts alongside the 95th percentile measure of latency, if available, to give you a clear summation of recent performance. Or you might plot the latency for each data center, or only for the 10 slowest hosts, to reduce the number of timeseries rendered.

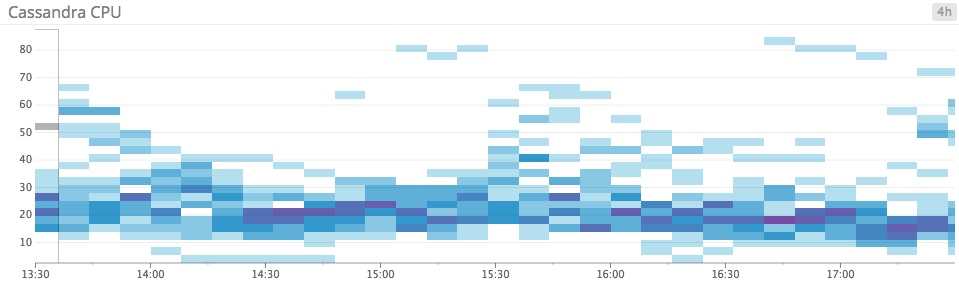

Heatmaps when trends matter most

For metrics such as CPU and system load, you may not have hard and fast thresholds, but you want to know when utilization is consistently high or low. Heatmaps are perfect for this use case because they clearly reveal group-wide trends and expose outliers, even for very large agglomerations of hosts.

An ounce of prevention

Many of the tips and guidelines outlined above are fairly common-sense, but that doesn’t mean that they are always followed. Even at Datadog, where we live and breathe metric graphs, a confusing or hard-to-read graph will occasionally pop up on our internal dashboards.

There are two unifying themes to avoiding common graphing missteps: First, before you build a graph, it’s worth taking a moment to ask yourself what you want that graph to tell you. As exemplified by the phyllo graphs, you can only pack so much information into one graph before things get bloated and hard to interpret.

The second theme is that graph types that work great for a few hosts (such as basic line graphs) don’t always hold up as you scale. Often the solution is to employ an entirely different graph type that is optimized for high-scale use cases, such as heatmaps. Alternately, aggregating to focus on key aspects of your metrics (such as medians or outliers) can steer a tangled line graph back toward clarity. Considering how much your infrastructure is going to grow, and how soon, can help you future-proof your dashboards and graphs.

We hope that the examples and suggestions described in this post help you build better dashboards to provide greater visibility into your infrastructure. With a bit of forethought, you can easily avoid the common mistakes described above. The result is clearer, snappier, easier-to-read graphs—and greater understanding of your metrics when you most need it.